Will Pay Rises be the Inflation Accelerant that Drives up Interest Rates?

Posted: 19/01/2022

Inflation is at its highest level in decades. Are we about to enter a 70s style wage-inflation spiral? The valuation of every asset class, including £2.2Tn of UK government debt, rides on the answer. But what causes higher pay claims and powers this spiral? We’ve been tracking pay rises since 2015 and we find that people are already responding to some types of inflation, such as commuting costs. Whilst there’s no spiral yet, we believe that one can form if household budgets come under enough pressure.

Recent ONS figures for Sept–Nov 2021 show wages rising at 3.8% per year. Given this is lower than inflation it means that wages are falling in real terms. Moreover, this annual rate is falling and inflation is climbing. The decline in real wages is accelerating. This squeeze doesn’t seem sustainable given low unemployment. So when will pay rises start to increase? And what will be their impact on inflation and thereby interest rates?

To explore this question, for the past six years we’ve been studying employee pay rise behaviours. Specifically, we’ve tracked how often employees request pay rises, what raise they’ve asked for, whether they were successful, and so on. But given people’s tendency to self-report socially desirable outcomes, we’ve undertaken this work using a clever anonymisation technique called unmatched count (UCT).

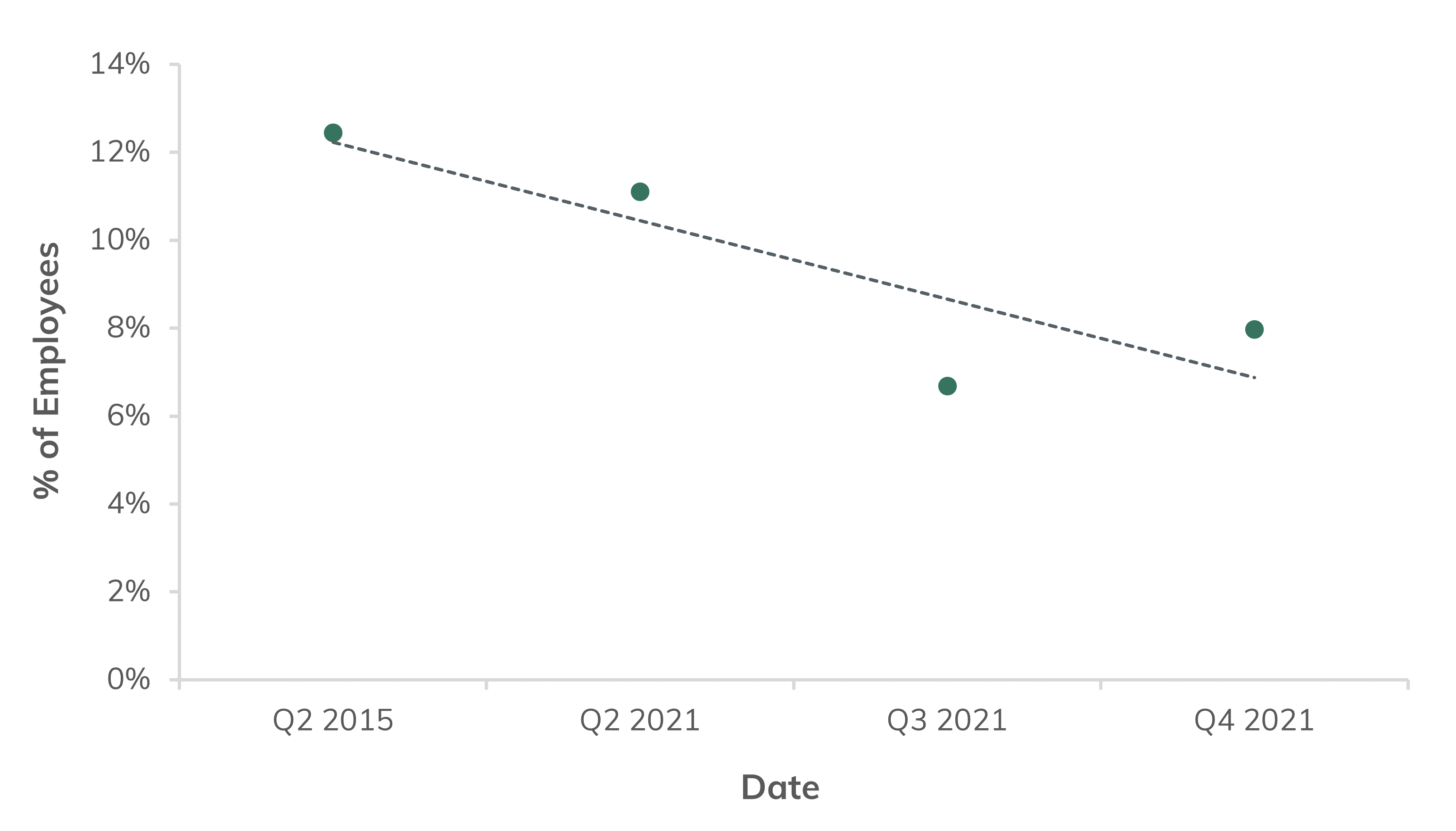

Figure 1: Real Pay Rise Demand Rate

Source: Dectech Research (N = 4,900 ; UK Nat Rep sample). Graph shows the percentage of employees asking for a pay rise when using UCT anonymisation.

The assumption that people flatter their responses when they aren’t anonymised is dramatically accurate. Asked directly, 31% of employees claim to have asked for a pay rise. In practice the actual rate is 11% and, as Figure 1 shows, this has been falling. Pandemic waves, and the associated employer disruption, employment uncertainty and increase in household savings, have suppressed pay rise demands.

Meanwhile, the percent of successful requests remains flat at 64% whilst the amount being requested is rising. In Q3 2021 the average demand by people on <£30k gross was +£1,350 (+5.5%). By Q4 this had risen to +£1,600 (+6.5%). In other words, the amount being requested is increasing, but not by enough to offset the fall in prevalence. In line with the ONS, our respondents’ salary increases are slowing.

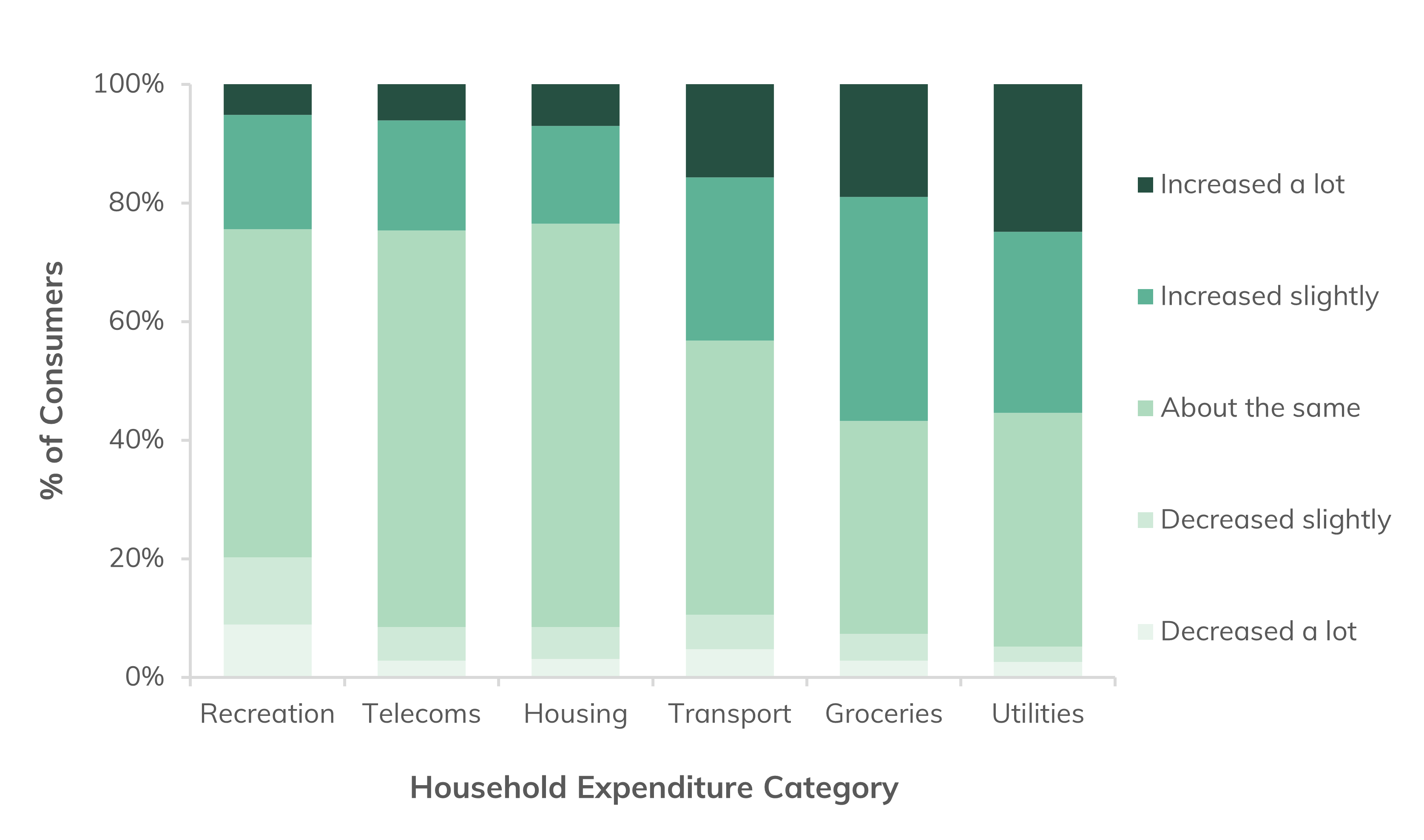

Figure 2: Recent Inflation Experience

Source: Dectech Research (Q4 2021, N = 1,270 ; UK Nat Rep sample). Graph shows responses to the question “In the last 3 months, has the amount you spend on the following changed?” using a five-point response scale.

So will the higher inflation rates being experienced in the UK, and globally, change this picture? Certainly, households are noticing inflationary effects. Figure 2 records how in Q4 2021 respondents were perceiving more price increases than decreases across all their outgoings. The highest levels of this “experienced inflation” are in Utilities, like gas and electricity, and Groceries.

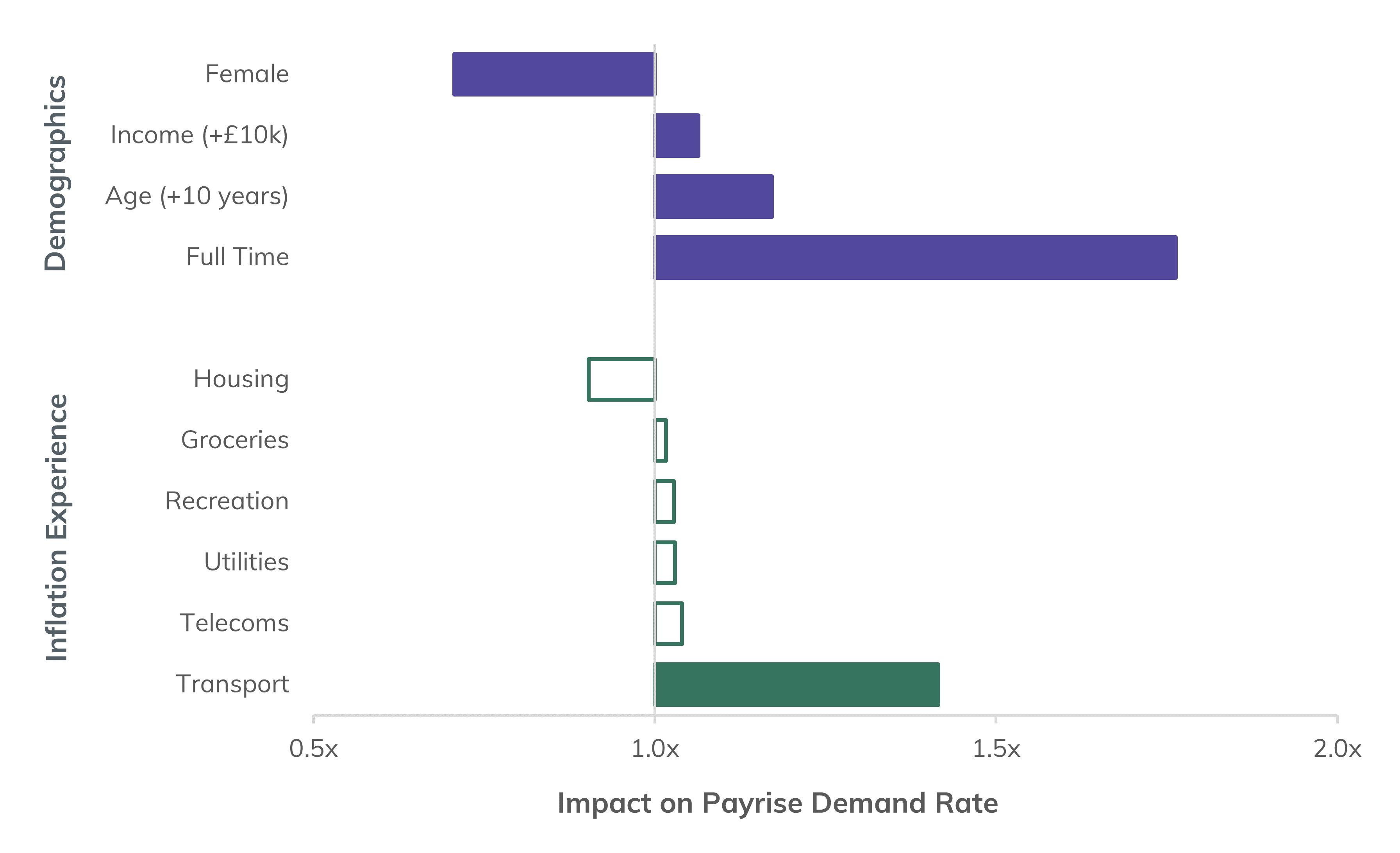

Figure 3 then examines what circumstances drives our respondents to demand a pay rise. For example, there are some demographic effects. Women request pay rises at x0.71 the normal rate. Likewise, full-time, rather than part-time, employees are much more likely to put in a raise request. This corroborates the earlier observation that pay rises are in part associated with perceived job security.

Figure 3: Drivers of Pay Rise Demand

Source: Dectech Research (Q4 2021, N = 1,270 ; UK Nat Rep sample). Binary Logistic regression with Pay Rise Demand as the dependent variable. Filled bars are significant at 10% confidence.

But the other key insight is the relationship with experienced inflation. As Figure 3 shows only one source of inflation is currently causing pay claims. Employees who perceive increased transportation costs, such as petrol and public transport, are x1.42 more likely to press for an increased salary. Inflation in all the other categories, including fast rising Utility bills, are not yet feeding through into wage demands.

So, we conclude that, at present people are only demanding compensation for costs they can justifiably attribute to their employment. This resonates with the finding we published recently that employers will need to pay a premium if they want people to commute into an office after the pandemic. In other words, household budgets haven’t tightened enough yet that people feel compelled to take the risk of demanding more money at work.

However, we forecast that this will change if inflation and tax increases bite hard enough in 2022. Eventually people will hear that demanding higher wages is an option. And if the pandemic has taught us anything, it’s that people’s behaviour is heavily influence by what they hear. Currently, we don’t see a wage-inflation spiral. But we do see inflation components influencing employee behaviour. It doesn’t take much imagination to see this influence widening. Maybe not on the scale seen in the 70s. But enough to prolong inflationary pressure and push long rates higher.